Découvrir

Éditorial

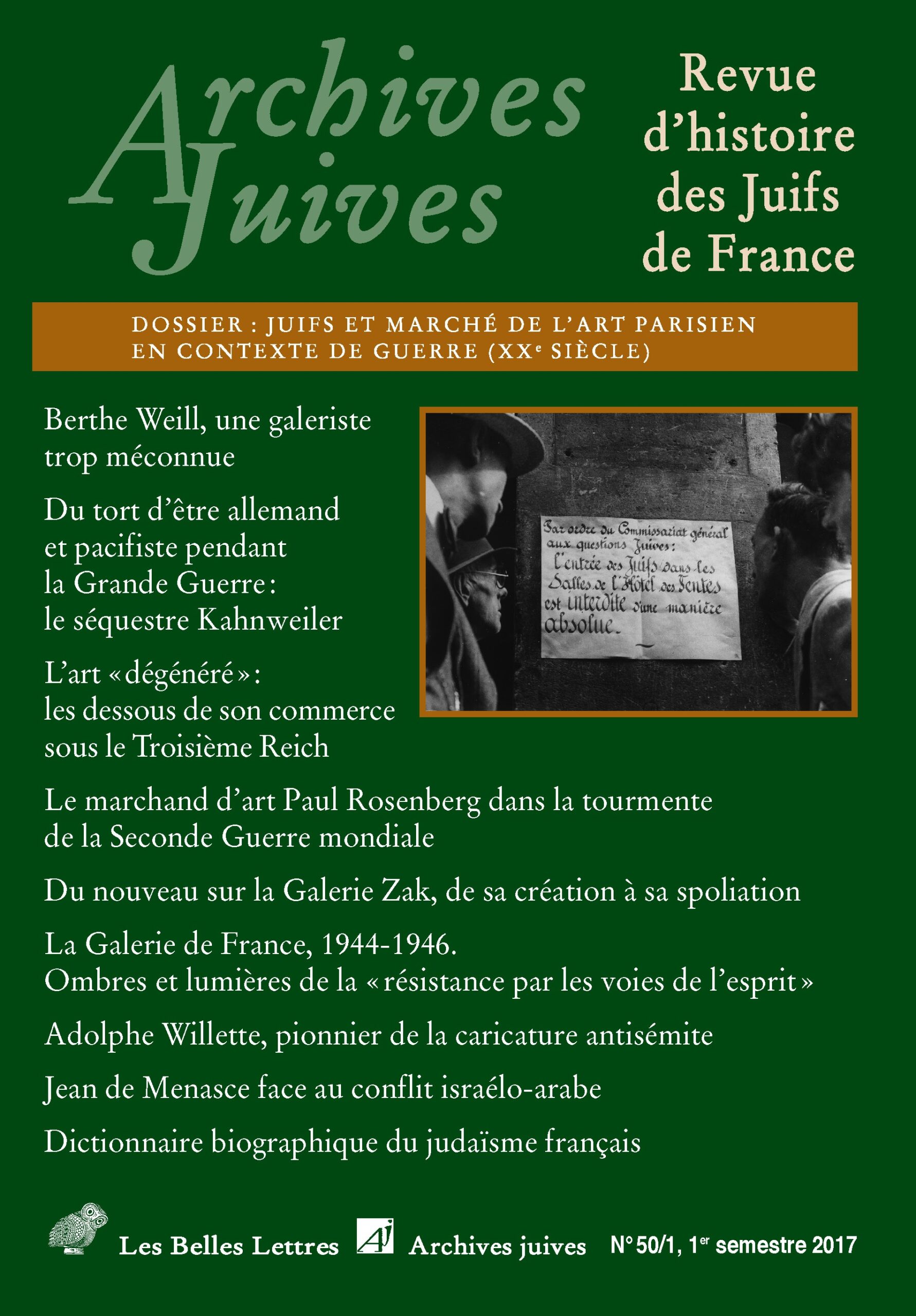

La question des spoliations d’œuvres d’art durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale et de leur restitution est partie de notre actualité depuis une bonne décennie. Outre les familles juives concernées, elle mobilise dans les universités, les musées et les ministères un nombre croissant d’historiens de l’art, de conservateurs, de juristes, d’archivistes et d’experts en tout genre. La complexité des problèmes historiques, juridiques et moraux qu’elle pose est en effet infinie. Il est rarement simple d’établir avec précision la spoliation et, quand les œuvres volées ont survécu et sont localisées, de retracer leurs pérégrinations très souvent transnationales. Et ne disons rien du problème, qui n’est pas du ressort des historiens, de savoir à qui elles doivent revenir entre les héritiers présomptifs, parfois fort lointains, et leurs détenteurs actuels, collectionneurs ou marchands qui peuvent être de bonne foi, ou Musées dépositaires, souvent anxieux de conserver des œuvres qui participent de leur renommée.

Il va de soi que ce dossier que l’on doit à Emmanuelle Polack et Yves Chevrefils Desbiolles, entourés d’historiens de l’art renommés ou prometteurs, fait une large place à ces affaires, d’autant plus nombreuses en France que Paris occupe, à l’époque encore, la première place sur le marché de l’art mondial. À côté des mécanismes de la spoliation, on remarque d’ailleurs l’attention toute particulière portée par les contributeurs au sort personnel des collectionneurs et galeristes juifs spoliés, très connus ou oubliés.

L’originalité du dossier tient toutefois à sa visée plus large. En aval de la séquence 1940-1944, il livre un aperçu sur l’après-guerre, les toutes premières investigations sur les œuvres volées et les premières restitutions mais aussi les débuts du travail de mémoire et la place « en creux » laissée dans la conscience des acteurs du marché de l’art par leurs collègues juifs éprouvés ou disparus dans la tourmente. Et, en amont, il incarne par des études de cas fouillées la place tenue dès la Belle Époque par des Juifs, français et étrangers, sur le marché parisien des avant-gardes artistiques, leurs origines, leur formation, leur sociabilité et leurs conflits, leurs réussites parfois extraordinaires comme leurs revers. Ces derniers seraient sans rapport, nous assure-t-on, avec l’antisémitisme souvent ambiant. On a un peu de mal pourtant à croire tout-à-fait que ces galeristes juifs aient pu être épargnés par des préjugés et des jalousies qui attendraient l’Occupation pour éclater au grand jour.

Sur ce chantier si actif, le dossier dresse, plutôt qu’un classique état des connaissances, une perspective stimulante sur la recherche en cours, celle qui gagne du terrain, jour après jour et non sans mal, sur une ignorance par trop commode et qui, à ce stade, laisse encore bien des interrogations sans réponses. C’est à la pointe du travail de recherche également que se situent les deux articles présentés au titre des « Mélanges » sur le caricaturiste Adolphe Willette et le père Jean de Menasce, un Juif converti en quête d’un difficile chemin d’équité face aux protagonistes du conflit israélo-arabe. Nos fidèles lecteurs retrouveront enfin, avec plaisir espérons-nous, les rubriques « Dictionnaire », « Lectures », et « Informations ».

C.Nicault

Sommaire

Dossier : Juifs et marché de l’art en contexte de guerre (XXe siècle)

Introduction par Yves Chèvrefils Desbiolles et Emmanuelle Polack

L’analyse du contexte historique et socio-économique de la production, de la diffusion et de la commercialisation des œuvres d’art est un thème de plus en plus prisé. Depuis une décennie, les historiens et historiens de l’art se sont mis en quête de nouvelles approches du marché de l’art, en développant des méthodes empruntées parfois à la sociologie de l’art, à l’histoire culturelle, ou encore à l’économie de l’art. Ce champ d’étude s’est inscrit principalement dans les xvii e, xviii e et xix e siècles, en raison, nous semble-t-il, de l’accessibilité des sources et de l’intérêt grandissant porté par les professionnels des Beaux-Arts à une meilleure connaissance de l’histoire des collections muséales qui leur avaient été confiées. La révolution de l’ère numérique amplifiant encore la tendance, des collections importantes ont été numérisées ces dernières années, proposant un accès en plein texte à de nombreux catalogues de ventes aux enchères publiques, permettant ainsi d’obtenir des jalons de provenance. À titre d’exemple, citons la base en ligne Art Sales Catalogues [1600-1900], les microfilms de la maison de vente Sotheby’s répertoriant les catalogues de ventes pour les années 1734 à 1970, la mise en ligne des catalogues du programme allemand German Sales 1930-1945 mené par la bibliothèque de l’université d’Heildelberg, moissonné par The Getty Provenance Index © Databases et, plus récemment, la mise en ligne, sur le portail numérique de la bibliothèque de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, des catalogues de ventes de l’hôtel Drouot concernant la collection de Jacques Doucet [1940-1945. Ces grands outils d’exploration du marché de l’art sont le socle documentaire nécessaire pour l’étude d’un champ de l’activité artistique qui se laisse difficilement circonscrire. Il est notoire que la discrétion, sinon le secret, entoure les mouvements qui animent le marché de l’art. Les parcours professionnels souvent atypiques des personnalités qui sont au cœur de ce commerce accentuent la complexité générale de l’ensemble. C’est vers le destin singulier de quelques-uns des acteurs du marché de l’art du xx e siècle – siècle guerrier s’il en fut – que nous avons orienté ce dossier d’Archives juives consacré au marché de l’art dans le contexte des deux grandes guerres européennes…

/ Summary not yet available

Une galeriste d’avant-garde sous-estimée : Berthe Weill, par Marianne Le Morvan

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ Berthe Weill: A pioneering yet overlooked gallery owner

Berthe Weill (1865-1951) was an important gallery owner of the modern period who has been largely forgotten. At the heart of the art market, she appears, in fact, to be intimately linked to the names of the most well-known artists of the period, such as Picasso, Matisse, and Modigliani. It is only recently that an archival collection documenting Weill’s acquisitions has been discovered. This previously unpublished documentation traces the contours of a career spanning almost forty years that was crucial in revealing major artistic currents from the turn of the twentieth century onwards. Extensive research has allowed us to learn more about her private life and situation during the Second World War. Berthe Weill is one of the rare pillars of the modern art market to have suffered relatively little from anti-Semitic persecution.

Les ventes de séquestre du marchand Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1921-1923), par Vérane Tasseau

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ The sales of art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s confiscated collection (1921-1923)

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884-1979), a German-Jewish art dealer known today for having discovered cubist art, amassed an incredible collection of more than eight hundred works by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Juan Gris and Fernand Léger between 1907 and 1914. During the First World War however, he was considered an enemy of France, because of both his German nationality and his pacifist stance. All the works in his possession were confiscated by the French government and sold at auction, with the profits filling the coffers of the treasury as war reparations. The four sales of this kind, which took place between June 1921 and May 1923, were an unprecedented event in the art world that merits analysis. This research also provides an opportunity to shed new light on Kahnweiler himself, an unfortunate merchant who overcame the worst of crises without ever ceasing to defend the artists he believed in.

Le commerce de l’art moderne sous le Troisième Reich. Un marché douteux, par Uwe Fleckner

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ Modern art dealing under the Third Reich. An unstable market

From the 1930s onward, in Germany, attacks perpetrated by the Nazi Party against the pictorial representations of the “expressionists” were of unprecedented violence, and repercussions on the art market were immediate. The artistic policy put in place by the Nazis in 1937 with the “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art) exhibition, the law of 1938 relative to the confiscation of the sale of so-called “degenerate” art, and the Lucerne auction in June 1939, succeeded in making modern art an object of public scorn. Current German historiography nonetheless allows us to clarify this story. The research of Uwe Fleckner describes a modern art market under the Third Reich in which works despised by the Nazis, which were nonetheless the object of speculation, were acquired through looting and despoilment carried out in occupied countries (Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands). Paradoxically, these campaigns of denigration against artists considered to be “degenerate” contributed to their recognition in the international art market after the war.

Paul Rosenberg, marchand des avant-gardes, dans la tourmente de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, par Emmanuelle Polack

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ Paul Rosenberg, dealer of avant-garde art in the chaos of the Second World War

In 1910, Paul Rosenberg opened an art gallery at 21 rue La Boétie in the eighth arrondissement of Paris. The art dealer, with visionary talent, alternated exhibits, presenting “classic painters” and the avant-garde. Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Rosenberg could boast that he had the two masters of contemporary art under contract: Picasso and Matisse. A victim of German ordinances as well as Vichy France’s anti-Semitic measures, Rosenberg quickly left France on June 17, 1940 to protect his family and immigrated (via Portugal) to the United States. Before leaving, he took measures to protect his personal collection and stock by moving them out of Paris. During the war, he continued his gallery on 57th Street in Manhattan, unaware of the extent of the spoliations of artwork taking place on the other side of the Atlantic, of which he was a victim. In the immediate postwar period, Paul Rosenberg began a difficult battle to retrieve his stolen works, some of which had transited through the Parisian and international art markets. He died in 1959, without having retrieved his entire collection, leaving his heirs with a hollow legacy and a fight to continue.

La Galerie Zak, 1926-1945, par Marc Masurovsky

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ The Galerie Zak, 1927/8 -1945

The Galerie Zak, located in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district of Paris, was founded by Hedwige Zak (née Jadwiga Kon), wife and widow of the Polish painter Eugeniusz Zak. In the Paris of the interwar period, the gallery quickly became an important place of artistic encounters. During the German occupation, Zak’s personal collection of artworks and that of her gallery were looted by Vichy officials. In 1943, she was arrested along with her son in the Nice area and ended up in Birkenau concentration camp where she was murdered. This article focuses on what can be said today of Hedwige Zak’s working life. The dynamism of her art gallery is clear to the researcher. However, it remains difficult to identify the personality of Hedwige Zak, who was, in her time, a renowned art dealer.

Critiques et galeries d’art, 1942-1946. Entre esprit de résistance et petits arrangements, par Yves Chèvrefils Desbiolles

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ Critics and art galleries, 1942-1946. Between a spirit of resistance and little deals

Over the past twenty years, research has shed light on the methods that ensured the prosperity of the art market during the Second World War: significant sums of capital flowed around, with the aim of making easy investments; a black market existed, stirred up by the fear of monetary devolution; and there was a glut of stolen works and reduced prices as a result of desperate Jewish collectors. Furthermore, Laurence Bertrand Dorléac’s pioneering research has shown the “meager courage and cowardliness” that characterized the wait-and-see attitude in the art world during the Occupation. Taking as examples the careers of art critic Gaston Diehl and art dealer Paul Martin, this article explores the way in which certain actors of the period, neither members of the resistance nor collaborators, slipped into a complex “in-between,” created by the sudden incapacitation of their Jewish colleagues. «

Mélanges

À l’origine de la caricature antisémite en France : le dessinateur Adolphe Willette (1857-1926), par Guillaume Doizy

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ Illustrator Adolphe Willette (1857-1926), the man behind anti-Semitic caricatures in France

We generally consider the caricature as a “major figure of anti-Semitic discourse” by focusing on periods during which the hatred against Jews was at a peak. An important fact must, however, be highlighted: until the 1880s in France, caricatures almost never depicted Jews. Iconography hostile to the “sons of Israel” only developed with the rise of Judeophobic publications. It was Adolphe Willette, one of the major illustrators of the late nineteenth century who developed, between 1885 and 1889, the vocabulary of the anti-Semitic caricature in France, combining Christian anti-Semitism, anti-capitalism, and racial characterization in a nationalistic logic that pitted the hated figure of the ugly Jew against the idealized Gallic figure.

Le conflit israélo-arabe importé dans l’Église : Jean de Menasce, une position d’équilibriste, par Anaël Levy

Voir résumé en anglais.

/ The Israeli-Arab conflict brought into the Church: Jean de Menasce and his balancing act

Jean de Menasce (1902-1973) was born into an upper-class secular yet Zionist Jewish family, and joined the World Zionist Organization in 1924. Baptized into the Catholic Church in May 1926, he became part of a pro-Zionist Catholic circle, which included Louis Massignon and Jacques Maritain. In 1925, the latter two tried to obtain the support of the Catholic Church for the Zionist movement, on the condition that the movement would argue for religious liberty and even an open attitude to Jews who had embraced Christianity. With the creation of the State of Israel and the Israeli-Arab conflict, Menasce opposed his two mentors, who were at that time in total disagreement with one another: he rejected both Massignon’s condemnation of an excessively nationalistic and materialistic Zionism, betraying Israel’s vocation, just as he rejected Maritain’s 1967 providentialist reading of the creation of the state. Menasce never stopped defending an intermediary position: that of the double legitimacy of national aspirations, in the name of natural rights, and the search for justice.

Dictionnaire

Armand Dorville, avocat, collectionneur (Paris 9e, 18 juillet 1875 – Cubjac, Dordogne, 28 juillet 1941), par Max Polonovski

Lectures

Maurice Garçon, Journal 1939-1945, Paris, Les Belles Lettres / Fayard, 2015